ON PAUL BOWLES: LIVING THE END

“One of these days the future will be here, and you won't be ready for it.”

― Paul Bowles, The Spider's House

I have wanted to write about Paul Bowles for a long time, and because he is a writer who explores endings, I consider him to be ghostly kin to the end times that ensnare us now. Covid-19 is an ending, or more accurately, an ugly coup de grace of things already done for. The virus is an insignia, the emblem of a terminus that actually happened long ago, which has now gone public at last. What author Hilton Als calls “this common world” is now done. And, with the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg this September 18th, we are all done for.

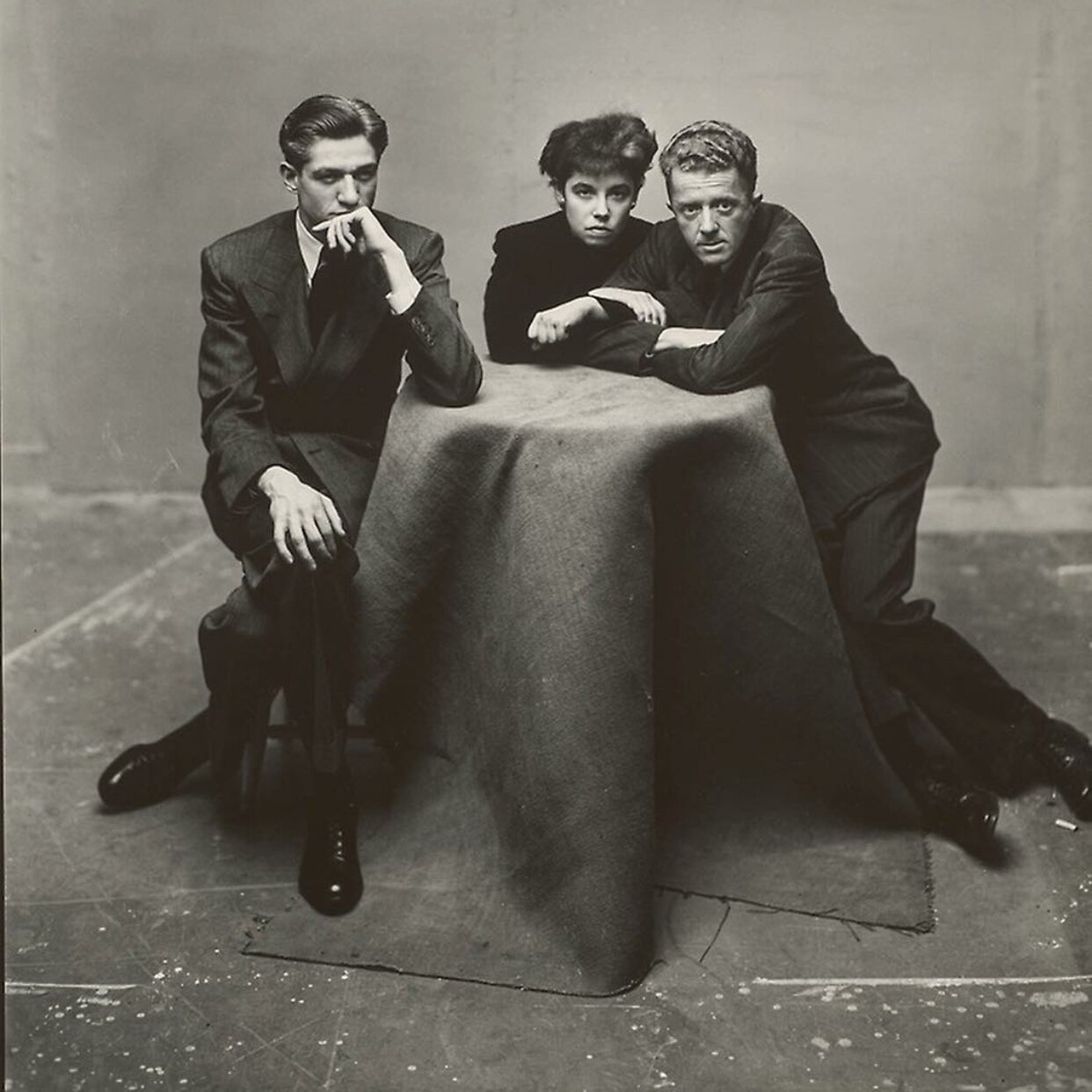

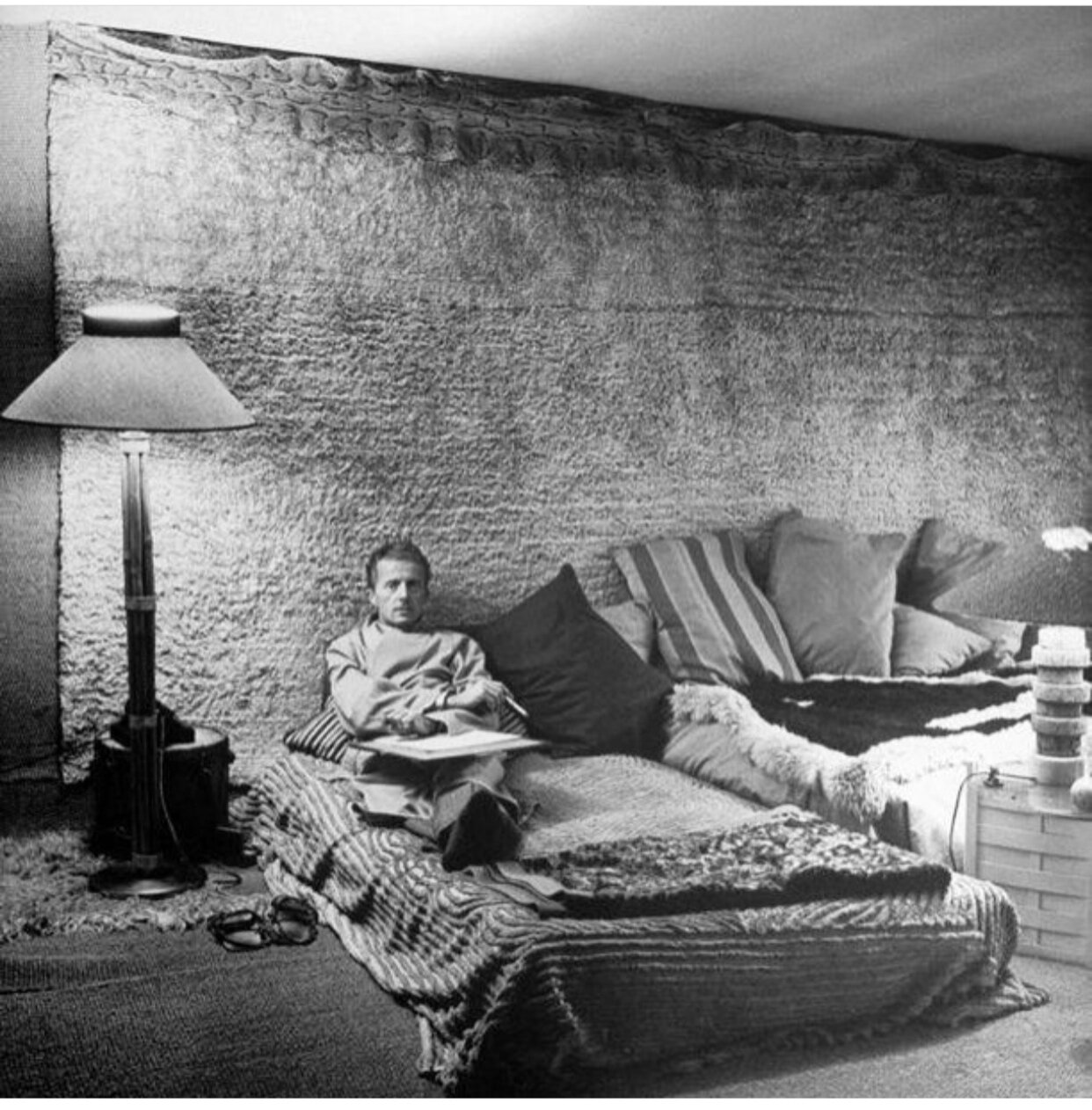

Photo of Oliver Smith, Jane Bowles, and Paul Bowles by Irving Penn, New York, 1947.

Still, we have the past. I wanted to reread my favorite novels and stories by Paul Bowles, whom I hold to be the greatest mid-20th-century American writer, my love for Truman Capote notwithstanding. Bowles captured and mourned the end of precious things, most poignantly the traditional culture of Morocco, which even as early as the 1950s Bowles felt slipping through his hands as he hastened to record it, in a losing battle against the machine of history. Bowles foresaw not only the end of traditional Morocco, but the end of all color, all variegation among nations and cultures. He would be revolted but not surprised by the present map of the world, pimpled with corporations by the millions.

This Bowles project I so long desired was recently prodded along by a friend’s adamant insistence that I read the 1964 novel, A Life Full of Holes, a book I’d never heard of, written, not by Paul Bowles, but tape-recorded, transcribed, and translated by him from a tale spoken by Driss Ben Hamed Charhadi—a North African street vendor and servant; eloquent, illiterate—in Maghrebi Arabic.

A Life Full of Holes is the first-person story of a Moroccan boy’s early life, measured almost from infancy by obstruction, senseless loss, and repeated injustice. Indirectly, by anecdote rather than instruction, the novels a long insistent look at what it means to live as a Muslim. If I understand the book at all, it is as the revelation of unconditional acceptance as the taproot of Islam. In A Life Full of Holes, there emanates from the narrator’s every misadventure, his serene, implacable certainty that each tribulation is Allah’s design for him. The words, “It is written,” are an unguent when things go wrong; a thanksgiving when they go right. To paraphrase this pronouncement in Christian parlance, even trouble possesses “that peace which passeth all understanding.” In contrast to Christianity, which interprets misfortune as either a test of faith or the punishment of sin, Islam ascribes grace and harmony to every turn of event, good or bad. Unlike Job, the Muslim does not argue with God, but searches out the right action along the path Allah unfolds for him, however mysterious and hidden its destination might be. The fate inscribed by Allah is not the damned if you do, damned if you don’t predestined march decreed by Martin Luther, but a winding plenitude of experience, some beautiful, some tormenting. If I understand correctly the version of Islam transmitted by Bowles, it is the Muslim’s duty to embrace and love one’s fate as an essentially merciful one—whatever its chasms—for Allah, above all, is all-compassionate, favoring mercy over punishment.

I have still to explore whether Nietzsche encountered Islam—a religion which delights in this world as well as the next—but in my own as yet faint and liminal pull towards Islam, I sense intimations close to Nietzsche’s creed of amor fati: his injunction that we love every joy and disaster in our lives so fervently that we would choose to repeat them—every iota—again and again through eternity.

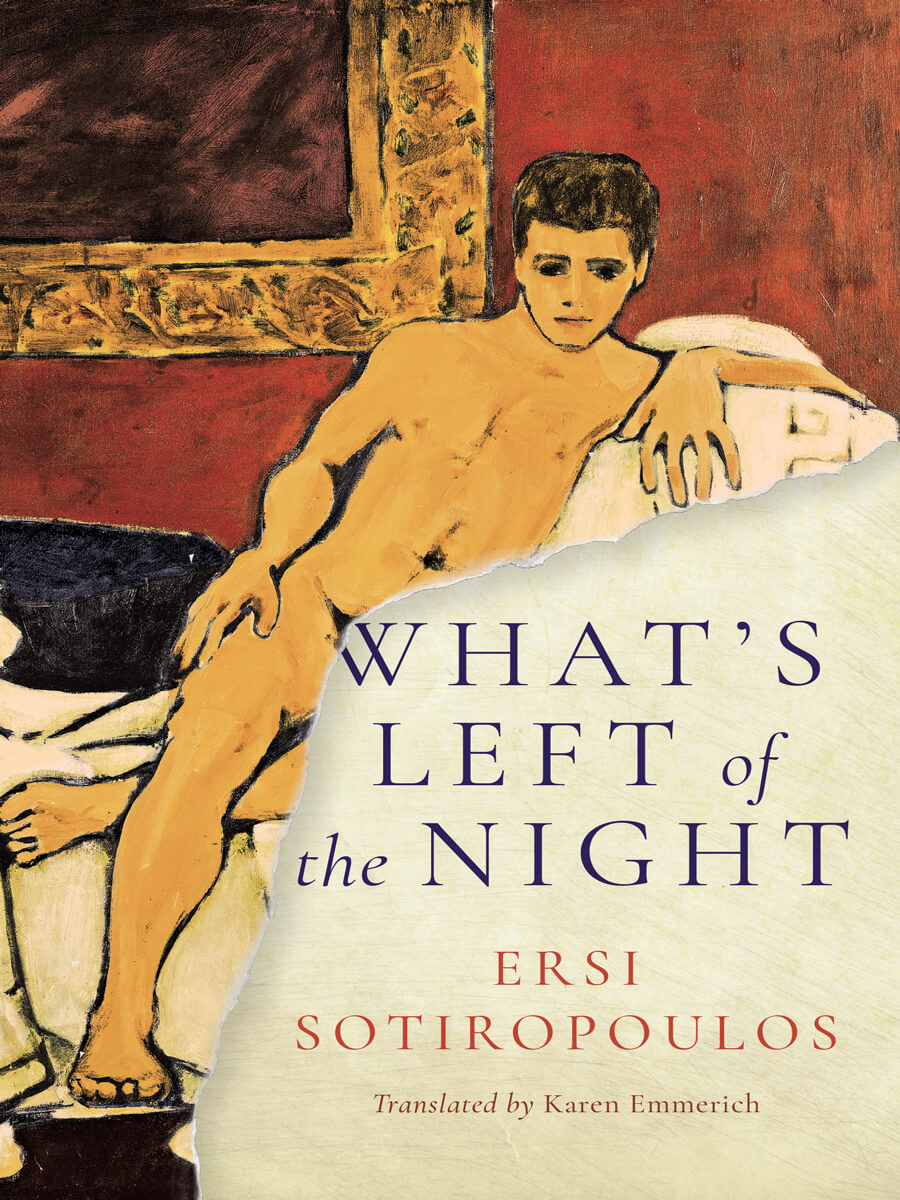

A second book which ruminates on Islam as radical acceptance—or indeed, “surrender”, the literal translation of the word—is by Paul Bowles himself. The Spider’s House, of 1955, is less famous and perhaps less formally perfect than Bowles’ earlier novel, The Sheltering Sky, of 1948. I love The Sheltering Sky for its taboo depiction of an American woman, Kit, who gives herself over totally to an omnivorous and indiscriminate sexual odyssey, after her husband dies in the Sahara. Seventy-two years on, neither literature nor pornography has equalled Kit’s episode: a prequel and rebuttal to the prissy excesses of #MeToo.

But it is The Spider’s House I turn to more often, for instead of psychic dissolution, it exalts mental power. If The Sheltering Sky is about one woman’s nihilistic undoing, The Spider’s House hides a lodestone of hope, or a heavy uncut jewel. I refer to the immutable force of character of Amar, the novel’s fifteen-year-old protagonist. In the novel’s last lines, Amar is betrayed and abandoned by his American friend John Stenham, an expat writer ensconced in a taxi with his vapid paramour, an American journalist and Communist wannabe called Polly Burroughs. Amar wants to travel to his mother and sister in Meknes, but the couple make hasty excuses and speed off, leaving Amar to the brewing political violence they are escaping.

We are left to ponder what will become of him, standing barefoot in the road. But from what we have learned of Amar’s physical courage and canny reading of people and atmospheres, it is clear he is no victim. Bowles doesn’t tell us, but my hunch is that Amar will reach safety with his mother and sister in Meknes. For he is equally immune to the epicene French, and to the drab, deracinated insurgents; vulnerable to neither.

Stenham, on the other hand, though long a denizen of Fez, can only straddle the fence between the French he abhors, keepers of Muslim culture though they be; and the Muslims who beguile him yet remain ever opaque, irremediably other. Stenham evades any intimacy with the many Muslims he knows. For them he feels admiration, sometimes awe, but never the warmth of human regard. Hence his rejection of the meeting of true minds offered by Amar, and his sloppy capitulation to Polly’s physical charms and insufferable self-importance. Polly has none of Kit’s daring. She is merely a bitch, just deserts for Stenham, whose only certainty in life is of his own damnation.

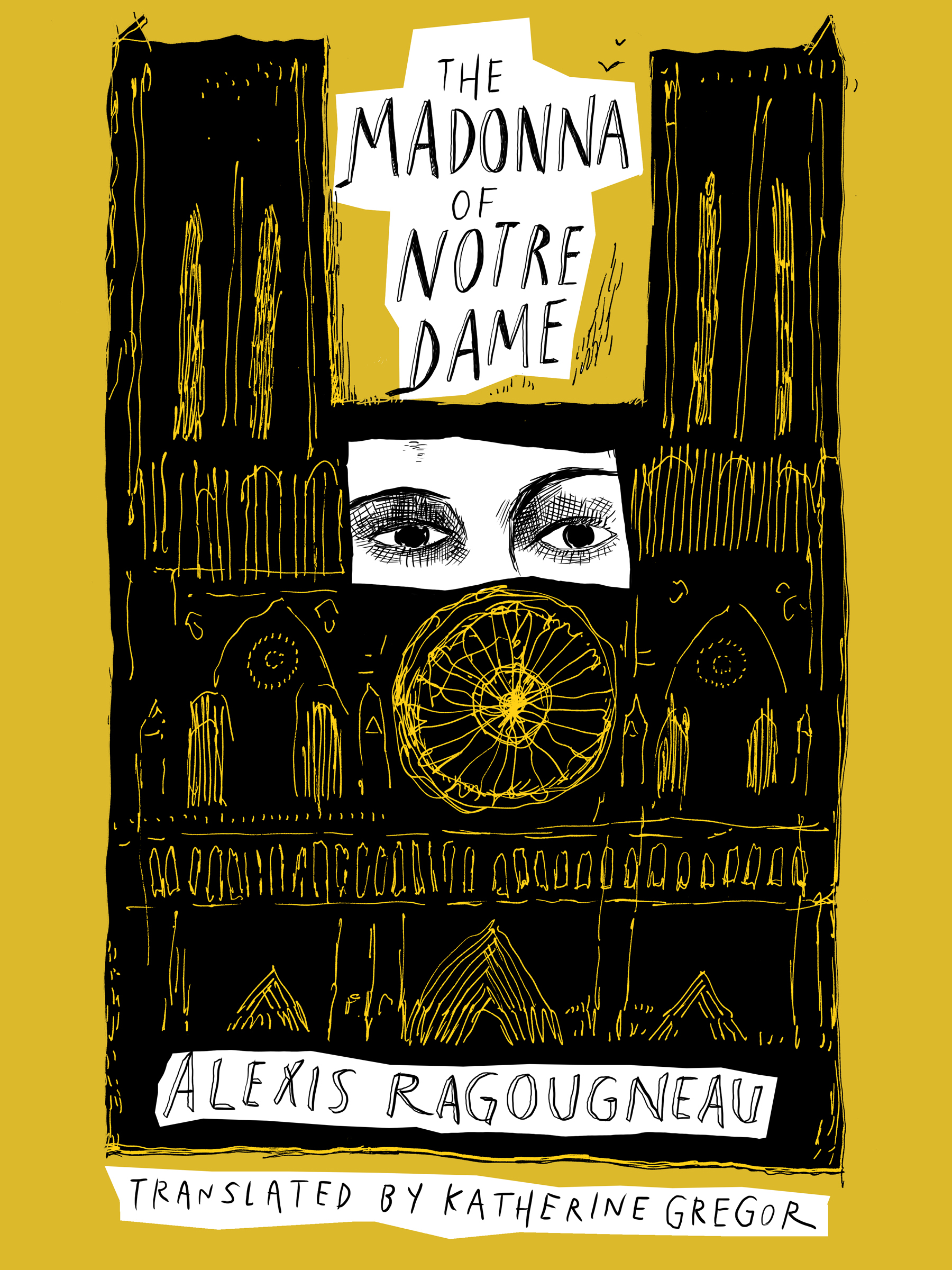

If we do not tremble for Amar at the end, Bowles leaves us shuddering at the wider fate of Morocco, for we do not tremble for Amar, Bowles leaves us to shudder at Morocco’s two-faced future: continued occupation by the parasitic French versus an independence shaped by soulless bureaucrats hell-bent on Polly’s “progress”. The exit of the French, with their Orientalist nostalgia for Morocco’s past, begins the end of Islam, dulling down the lustrous secretive beauty of Morocco’s persons, places, and things, a beauty that follows directly from Islam.

When the built world of the sacred succumbs to secular systems, signaled by concrete towers, the incumbent spirits of place depart, seeking out cities crumbled beyond repair, or primordial landscapes layered with petrifications of the remotest past. Auras, too, can migrate, encircling rediscovered bodies and buildings hospitable to ancient truths.

Like Bowles himself, while writing The Spider’s House, Stenham knows he is living off the last morsels of the Medieval Moslem world. He inhabits a borrowed home—a French hotel, as it happens—and lingers there on borrowed time.

“When I first came here it was a pure country. There was music and dancing and magic every day in the streets. Now it's finished, everything. Even the religion. In a few more years the whole country will be like all the other Moslem countries, just a huge European slum, full of poverty and hatred.”

In Arabic, the concepts of love, mercy, and kindness--rahma--share a single etymology, derived from rahim, meaning “womb.” Compassion—in Arabic a synonym for love—is a protection as essential to us during this pandemic as the masks we must wear. Like Mary Magdalene, we should spill out love like the spikenard she splurges on for Jesus, with extravagance and generosity with whomever we shelter-in-place: working, learning, loving.

Mercy, like Islam itself, affirms this world; this life. This common world—stricken and defiled—may yet be healed by devotion to its wonders, awe for the beauty that streams from it still. It is high time to tend the only Paradise we are certain to know.

![[Left] Linda, Alison Cornyn, Linda was committed to the Training School in 1921 for being an “ungovernable or disorderly child” at the age of 13. Pigmented ink on archival paper, 2013. [Right]American Dream Beth Thielen. Charbonnel ink mono-prints o…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56789f2fd82d5ec4289f5e25/1552157802865-ILDKHAF9J3RQ1738U7CN/20-Incorrigibles_Installation_NKB1814-Edit-72.jpg)