THE MIND OF A CITY

By Lisa Zeiger

The Newark Public Library, photograph by Jim Henderson.T

“People can lose their lives in libraries. They ought to be warned.”

--Saul Bellow

Within each of the six cities I have lived in, there was always one public building that claimed me; one that stamped my citizenship. In Glasgow, it was Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s quixotic School of Art of 1899. In New York City, I confess it was Barney’s clothing store at 61 Madison, the design of its interior altered every few years, reaching its apotheosis in the late 1990s via the work of my friend, artist-gone-survivalist, John-Paul Phillippe.

The Glasgow School of Art.

I have only ever been a citizen of cities--one at a time--and, frankly, felt no belonging, identity, or allegiance whatsoever to America as a whole. Not, that is, until now, when America’s freedoms--like electricity, taken for granted--are no longer invisible, infinite conveniences, but stony landmarks, smaller than we thought: chipped, hacked, and poised for demolition.

I lived in New York City for over four decades--with breaks in Europe and L.A. that lasted years--until 2017. I left because I was a pauper, working two jobs and made homeless at 59 by the “gig economy” and its ridiculous multi millionaire puppeteers. Now, in Newark, which I pray is too poor to ruin, I inhabit a boarding house. Yes, we still have hundreds of real ones here, unadorned by the bronze plaques--which might as well mark tombs--that in New York indicate the houses where Walt Whitman, Edgar Allan Poe, Willa Cather, Stephen Crane, Theodore Dreiser, and O. Henry, once rented just one room. These famous names are but a fraction of the writers who flowered thus. Such is my home in Newark. In it, in nine months, I wrote my first book, now in the hands of an agent. Within its narrow walls, I no longer fear my death: I plan it with pleasure.

In the chain gang of Manhattan talent, which stretches for miles, I would have settled, as many do, for Warhol’s fifteen minutes of fame. In Newark, I’ve switched to the long game: books which attain a footnote in posterity, my personal dream of the afterlife. If my readership doesn’t gather till I’m gone, it’s all good. I’ll make merry in my grave, just as a few creative New Yorkers laugh all the way to the bank.

In downtown Newark, two buildings away from the Greek Revival Museum on Washington Street, there is another edifice which yanked me in like a church; my faith instantaneous and ardent. The Newark Public Library, designed around 1898 by John Hall Rankin and Thomas M. Kellogg and opened in 1901, is above all a place. My adoption of and by this four-story limestone Italianate building, inspired by the 15th century Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, was settled the second I walked in. In Newark, I did not yet know I was home; but the Public Library was my manifest embassy. I had found, by chance, exactly the right city--ennobled as it is by this institution--for the little life I passionately want. Writing requires adventures in the past--these days, hideously called “content”--and limits in the present. The latter for me are severe and voluntary.

I have had other embassies, other shrines; but just as M.F.K. Fisher named both her final residence and her final book “Last House,” so have I made an uncharacteristic commitment to Newark till death do us part, a loyalty that comes straight from the Library, like a book--or a heart--forever stolen, not loaned.

That’s enough personal preface. The Newark Public Library has its own evolving biography, with heroic humanist adventures and achievements I will attempt to outline in this brief account. A more diligent researcher should one day write a book connecting the 120 years of stories, some of them esoteric, housed inside it.

The architects’ intentions were to create a building beyond a library, designing the space to serve also as museum, lecture hall, and gallery. Rightly, they ensconced book learning in the wider unity of visual culture so well understood in the late 19th century, expressed by an architecture and interior that seduces the visitor towards self-education by pleasing the eye.

The building structure includes an open center court with arches and mosaics that extend upward to a stained glass ceiling four stories high. Over the front entryway is the bronze relief, Wisdom Teaching the Children of Men, sculpted by Newark artist John Flanagan, installed in 1909. In 1927, the Friends of the Library commissioned the artist Robert Hales Ives Gammell, a Classical Realist and member of the group known as The Boston Painters to paint a mural. The Fountain of Knowledge was unveiled on the east wall of the second floor and depicts a group of sages, the Fountain of Knowledge, and the Nine Muses. The Muses, daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne, are accompanied by Apollo, transporting knowledge to the four corners of the earth. In the far left corner hovers a likeness of John Cotton Dana--founder of the Newark Museum--who also served as the institution’s librarian and influential second director until his death in 1929.

Gammell’s pale, etheric murals have always echoed for me those of the 19th century Symbolist painter, Puvis de Chavannes; reminders that reason and knowledge, pace Freud, originate in the Divine, even for those, like Freud, who would use that knowledge to explain it away. Like Prometheus, every reader steals fire from heaven.

The name Newark, when Americans elsewhere think of it at all, evokes the 1967 race riots, and more currently, dimly understood crime statistics and rumors. What few people know--myself included, till I moved here--is that Newark is one of America’s oldest cities, founded in 1666 by Robert Treat, who led a group of New Haven Colony dissidents to New Jersey, having been forced by the Connecticut Charter to merge with Connecticut in 1665. Newark was but an interlude in Treat’s long, peripatetic military and political career, but he is said to have brought to his new city dozens of books, including the Bible and other, probably Puritan, religious tracts.

The beginnings of a library proper occurred much later, when an 1840s law resolved to establish a library in built form. From 1845 to 1889 this mission was incrementally carried out by the Newark Library Association, first from its landmark home, Library Hall, a cultural fulcrum also housing the post office, the New Jersey Art Union, the New Jersey Historical Society, the New Jersey Natural History Society, and the YMCA. Library membership among the public was by annual subscription of $3.00 until an 1884 state law, upheld by voters, galvanized the establishment of a free public library. The Library Board of Trustees was formed in 1888; and its first edifice, on West Park Street, opened in 1889.

Even before 1899, when the cornerstone of the present Newark Public Library was laid, Library Hall was a veritable ambassador of written and sometimes visual culture in Newark. It acquired books in foreign languages, as well as donations of important private collections; organized the University Extension Society in 1893, inaugurated by an exhibition of art books; appointed professional librarians, first, Frank Hill, then Beatrice Winser, later the assistant to John Cotton Dana, appointed Director in 1901 and Head Librarian in 1902; and last but not least, delivered books by wagon to Newark’s schools and firehouses.

The Newark Public Library as a solid, enduring palace of books was opened officially in 1901 by Librarian Frank Hill. All that transpired at 5 Washington Street from that earliest of 20th century dates was incalculably enriched by the legacy of the decades immediately preceding: a long period of unusual and abundant flowering in all the arts, and moreover, the social will, in both Europe and America, to shape from them a unity that would benefit society as a whole. Political utopias always fail; but history is kinder to artistic movements. The latter’s fluid cultivation of both the individual artist and of a diversity of groups, each formed around a shared aesthetic insight, but none of them dominant, is the very opposite of political movements--even those dedicated to equality and freedom--which prevail only through the imposition of order, often a rigid one at that, their unity all too often achieved only through a potent, charismatic leader. As Hannah Arendt would write much later in the century, in the wake of World War II, “good” authority is “something between a suggestion and an order.”

Late 19th and early 20th century art movements evolved and magisterially succeeded through powerful visual suggestions, ranging from color theory, some of it based on Goethe’s treatise, Die Farbenlehre; to the unbuilding of the subject through Cubism and Futurism; to the beginnings of pure abstraction in Kandinsky, Hilma af Klint, and Paul Klee; to spiritualistic attempts--some Christian, some not--to contact other worlds and channel the visions they revealed into works of art. At the same time, Nietzsche’s often misinterpreted declaration that “God is dead,” cast a long secular shadow; cemented by Freud’s deconstruction of religion’s “oceanic feeling” as psychological defense rather than manifestation of a real if inchoate divinity.

In art, a medley of these heady, often conflicting ideas permeated even American pragmatism: hence, Gammell’s mythic, frankly pagan murals, and the Library’s focus, from the beginning, on visual art as the sister of written texts. The Library’s opening was launched with an exhibit of materials loaned by Charles Scribner, the New York City publisher. Director John Cotton Dana began Newark’s own picture collection, and staged a major library art exhibition in 1903, attended by an astounding 32,000 visitors. In 1910, the Art Department moved to the third floor with a large collection of 7,000 books. 1915 saw an important exhibition on New Jersey ceramics; in 1916 a great textile exhibition coincided with celebration of Newark’s 250th anniversary. A major exhibit on printing followed, featuring Bruce Rogers, and co-sponsored by the Carteret Book Club, founded by Dana in 1908, the same year the Library staff came under Civil Service rules.The year 1920 brought an astounding new Library service: fine art prints were circulated to borrowers with “library-approved frames.” In 1921, a bronze plaque honoring the brief, tumultuous life of writer Stephen Crane--born in Newark in 1871, dying in 1900, only a year before the Library opened--was affixed to the building facade.

Dana also made of the Library a veritable publishing house, producing Frank Urquhart’s three-volume history of Newark in 1904, among other books printed during his administration. Books for the blind were made available; five Italian-language newspapers were subscribed to for the large Italian-speaking community; and new branches opened in other districts of Newark, notably the Springfield or ‘'Foreign Branch,’ with books in Russian, German, Yiddish, Polish, Ruthenian, Italian and Hungarian. In 1906 the U.S. document and U.S. Patent collections, among the largest in the country, were begun; and in 1907 the telephone came into use as a serious reference tool. The Library was the stage for a major city planning exhibition, with maps, charts and graphs, in 1912. In 1914, the color-coded filing system developed by the Library became standard for other American libraries.

John Cotton Dana (1856-1929) and Head Librarian of the Newark Public Library from 1902 until 1929.

During the First World War, the Newark Public Library became more activist than oasis, sending in 1917 41,000 books and 200,00 magazines to servicemen in Europe; in 1918, working with wartime organizations in town.

In the 1920s, the Library augmented its collections of valuable rare books, acquiring that of J. Ackerman Coles; engaging Shigeyoshi Obata, Japanese print and book expert, to identify materials in Newark's famed Japanese collection; and publishing book lists on the Far East.

In 1929, John Cotton Dana died, and Beatrice Winser was appointed Librarian. The Great Depression ushered in serious cutbacks in the early 1930s, including the closing of branches in hospitals, schools, and jails. But 1935 brought the relief of WPA activities, salary increases for the lowest-paid employees, and by 1937 significant increases in the operational and book-buying budgets.

The seminal account of the Newark Public Library during and after World War II is Philip Roth’s June, 2017 essay in the New Yorker, written almost a year before he died.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/06/05/i-have-fallen-in-love-with-american-names

The title, “I Have Fallen in Love With American Names,” tells a story in itself: Roth’s passionate absorption, as the grandchild of 19th century Jewish immigrants, in regional writers, none of them Jews, “mainly small-town Midwesterners and Southerners...shaped by the industrialization of agrarian America” which began in the 1870s.

Roth’s teenage reading list after the war included Theodore Dreiser, born in Indiana in 1871, Sherwood Anderson, born in Ohio in 1876, Ring Lardner, born in Michigan in 1885, Sinclair Lewis, born in Minnesota in 1885, Thomas Wolfe, born in North Carolina in 1900, Erskine Caldwell, born in Georgia in 1903--all emissaries from a “second world” who lifted Roth’s “ignorance of the thousands of miles of America that extended north, south, and west of Newark…” These authors imported geographical nuance to Roth’s grade school inculcation, from 1938 to 1946, with “the mytho-historical conception of my country.” The American effort during World War II had harmonized an extraordinary “marshalling of communal morale,” which becalmed, for a time, the country’s seething conflicts of national origin, ethnicity, religious difference, class, and race.

The sentence in Roth’s essay which particularly captivates me recalls his high school years, when “... I began to turn to the open stacks of the Newark Public Library to enlarge my sense of where I lived.” Today, the Library’s stacks, still open to the public, constitute a densely material intellectual resource I have not encountered since the late 1970s at Barnard and Columbia, a rare access to tangents of book learning I suspect is disappearing from the life of libraries at large. Wandering the stacks of Columbia’s Butler Library in search of a particular call number, I invariably made new literary acquaintances side by side with whatever book I’d set out to find. This purposeful yet rambling forage spiked agenda with accident. For the most inspired research is not limited to the texts we expect to find, but admits as well their long-lost relatives, books just lying in wait in the stacks for us to check them out, in both senses.

Roth willed his books to what will become the Philip Roth Personal Library, a grand reading room on the second floor with arched windows. The $1.5 million cost of the project is being raised by private donations to pay the architects, designers and construction firm already hired. Rosemarie Steinbaum, a dean at Joseph Kushner Hebrew Academy in Livingston chosen by Roth to curate his Library legacy states, “It is an astounding opportunity not just for the Newark Public Library but for Newark.”

An exceptional testimony to the irreplaceable power of library stacks, is the work of the late artist Jerry Gant. As a young man, without any formal art training, Gant spent hours in the Library stacks going through hundreds of art books teaching himself what he needed to learn to make his own art work. He was much beloved by the Library, which will pay tribute to him by installing the book sculptures he created for the Cafe, slated for February, 2019.

The late Jerry Gant’s book work, shaped from discarded books and destined for display at NPL’s cafe.

In February 2017, the distinguished librarian Jeffrey Trzeciak was named Director of the Library, arriving from his post as University Librarian at Washington University in St. Louis. During Trzeciak’s thirty-year career in urban libraries, he has been a champion of civil rights and social justice, particularly in the African American, Hispanic and LGBTQ communities. He possesses an acute, potentially controversial awareness of libraries as loci of political engagement, as well as storehouses of “objective” information. Given the present White House attempt to annihilate public schools, public libraries are our surviving arenas of learning, tailoring ever more educational activities to the children and teenagers of diverse communities for whom private schools are a commodity out of reach.

Since coming to Newark, Trzeciak has cast a wide, necessary net of extra-literary community outreach services, some intensely practical and urgent, as in the Library’s donation to homeless citizens of backpacks filled with toiletries and writing materials; and its food drive, which forgave borrower fines in exchange for canned food, destined for the Newark Food Bank. (The Library has now abolished fines altogether.)

Then there are pinnacle literary events, most famously the September 2018 Philip Roth Lecture delivered by Salman Rushdie. Between the poles of emergency and enlightenment are an almost daily calendar of arts and crafts lessons and reading groups for children, and evening readings and discussions with authors for adults, often targeted towards the upcoming generation of readers, as in the April 2018 overflow audience for Dominican-born writer Junot Diaz’s bilingual reading and signing of his children’s book Islandborn (Lola in Spanish). On Friday evenings in summer, the adjacent garden hosts live music with dancing, the most memorable a Cuban party where cigars were hand-rolled then handed out, along with homemade Cuban delicacies.

Public libraries, like museums, must snare corporate donors for their survival, and crowds for their vitality; as well as to justify their very existence for government funding. And now, as historically, the Newark Public Library houses and displays much more than books to attract the community it sustains. Its art exhibitions in the past year have traversed the overtly political, as in the photographs from “Ferguson Voices: Disrupting the Frame”; to more traditional exhibits of images and artifacts central to local history but obscured by time and demographic change, notably “Synagogues of Newark: Where We Gathered and Prayed, Studied and Celebrated”; and “‘Old School’: Collections of the Newark Public Schools Historical Preservation Committee.”

Jennifer Blum is a Librarian and Adjunct Professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York, and an intensely driven board member of sixty-some Friends of the Newark Public Library. The Friends are a cadre of volunteers who raise funds through sales of deaccessioned and donated books; are initiating a program to support children’s art projects at branch libraries; donate numerous Spanish-language children’s books; and have established a social linchpin, namely The NPL Cafe and Friends of the NPL Bookstore, where even massive art monographs can be had for a dollar.

Already transfixed by the building, I discovered in Jennifer a human conduit to the Library’s mission. The day of my first visit, flyers advertised a book sale on the fourth floor, a shopping spree I couldn’t resist. Books were the last luggage I needed, as I was still living in a shelter, awaiting the move to my present boarding house. For two dollars apiece, however, I stashed heavy classics beneath my cot: thick art books that included The Dream Come True: Great Houses of Los Angeles, by Brendan Gill and Derry Moore; The Machine Age in America: 1918-1941, published years ago by the Brooklyn Museum and Abrams; and The Parallel Worlds of Classical Art and Text by Jocelyn Penny Small.

My interest in this third book elicited from Jennifer the revelation that she had studied Classics, first at U.C. Berkeley, later transferring to and graduating from NYU. She then earned an M.A. in Medieval Islamic History from Brandeis. Only a hundred years ago, if that, nobody was deemed truly “educated” without a passing knowledge of Latin and Greek. This once-mandated mastery of half-lost, sophisticated structures, especially ones so archaic as to seem alien, instill a method for understanding just about anything. Several graduates in Classics I have known, mostly British, leapt with almost unfair ease from the study of Latin and Greek to spectacular success in unrelated but equally fascinating professions: examples are MoMA curator Juliet Kinchin, and labor lawyer Nicola Dandridge, now a Commander of the Order of the British Empire.

I began this essay with examples of the power of great buildings to make us feel we belong; and the paradoxical power of humble surroundings to make us know we can write. It is this second quite idiosyncratic conviction I’ll conclude with, remembering always, as a writer in one room, that my work is indispensably abetted by the nearby Newark Public Library, whose splendor I can borrow whenever I want.

In Newark, people without a penny laugh as they live, following inflexibly the first commandment of the hood: Mind Your Business. Books are so much easier to write far from the backstabbing crowd. The voice I hear now is my own, uncontaminated by the bad grammar of celebrated, usually bourgeois writers who know better, but think the massacre of language is democratic, politically correct, and above all, “edgy.” What they don’t know is, the hood they talk down to craves the grammar they were deprived of in school, a valuable addition to their own vernacular; not its replacement. When both schools and literature abandon age-old rules of speech and writing that work for new ones that neuter, it is left to the still-open, still-uncensored stacks of libraries to replenish the sentences we utter and write.

Unfair passions and rage, pungency and extremity--that of Shakespeare; of Richard III and Macbeth--are as native to the English language as prayer. And the latter, at its highest, is never anodyne, euphemistic, or casual. Thomas Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer was a speech act that got him burnt at the stake. His words incite us, with the grandeur the task demands, to change our lives completely.

When language, with the best of intentions, is forbidden to burn, it burns out.

Travel the stacks.

POSTSCRIPT: THE ENDURING ALLIANCE OF THE NPL WITH THE VISUAL ARTS

As the brief history of the Newark Public Library above emphasizes, from as early as 1920 the Library is has sought to disseminate knowledge of works of visual art along with with written works. The Library’s annual fundraising gala, “Booked for the Evening,” on November 19th, 2018, featured not only speeches by honorees whose support for the Library has been exceptional, but a small silent art auction, to benefit the sixty-strong Friends of the Public Library, the voluntary organization who supports its mission with outreach and donations, among other activities. As curator, I gathered some eight works either from artists I knew well, or from talents discovered on Instagram. I intend, in future, to expand greatly this event, focusing upon the strong and evolving community of artists in Newark itself.

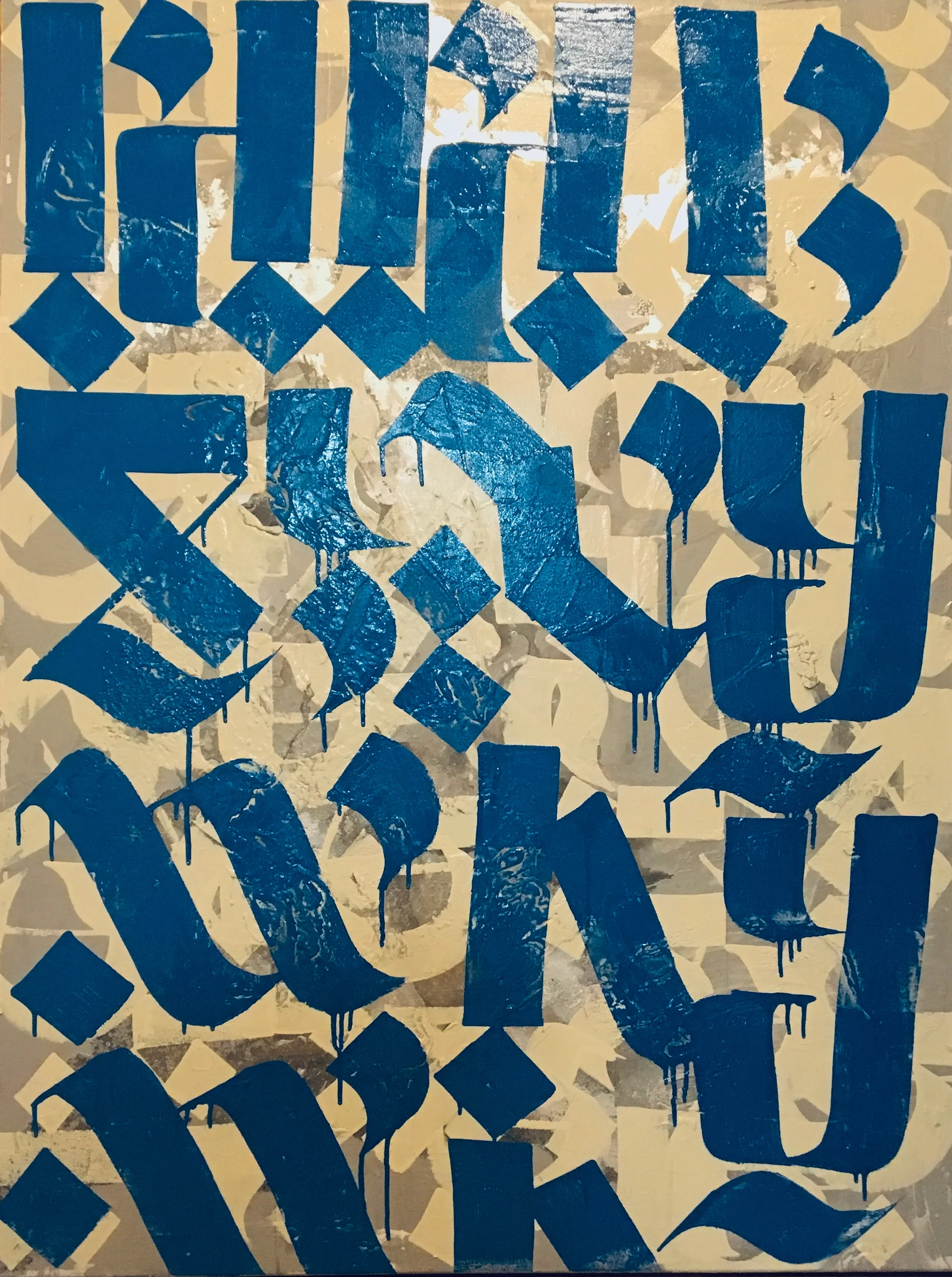

The undisputed centerpiece of our small array was New Jersey artist David D. Oquendo’s large calligraphic painting, “I Did It My Way,” enamel and spray paint on canvas; blue letters on silver, grey and white background. California artist, Alan Good contributed a labyrinthine lithograph, “City Lights”; and East Texas photographer, Courtney Marie Musick Harvey, donated two small black and white prints, “Osmosis,” and “Summer.” (I consider Courtney to be a cross between Diane Arbus and Sally Mann.)

“City Lights,” Lithograph by Alan Good (2017)

“Osmosis,” by Courtney Marie Musick Harvey

Dutch-Argentinian photographer Richard Koek, recent author of the monograph New York, New York, donated the color photograph “Terrace on the Park, Queens”; and upstate New York painter Peter Cusack gave us a lyrical sepia nude on paper. Contemporary art collectors Susan Manno Wood and Alexander Wood donated a small, unexpected icon of tradition: a porcelain Tiffany box.

One more donation, the 1945 etching, “Roman Head,” by Frederic Taubes (1900-1981), was donated by New York curator Alan Rosenberg, in honor of the prodigious William Dane, the head, for 62 years, of the Library’s Special Collections Division. A founder of the Victorian Society in America, Dane and Rosenberg met while the latter was serving on the board of directors of the Metropolitan Chapter. Recounts Rosenberg,

“William Dane was a founder of the Victorian Society in America and we met when I was serving on the board of directors of the Metropolitan Chapter. I asked him if the Newark Public Library might have any information on Edward John Stevens, Jr., a Newark artist who was the Director of the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Art in the 1950-60s. Not only did the library have an extensive file on the Stevens but Bill knew him well. Not only was I able to find the information I needed in my research but I also got to hear a number of personal anecdotes about the artist. BillDane was a charming person whose life mission was to share the voluminous information that he had at his fingertips and in his head.”

For further information on David D. Oquendo and Courtney Marie Musick Harvey, please take a look at my blog posts on them, at www.bookandroom.com. Mark my words; they are up and coming.

Such is the polymath expertise harbored within the precincts of the Newark Public Library.

Frederic Taubes, “Roman Head,” 1945